(Greece, Egypt, India, South Yemen, China, Rome)

A number of things made the Nabataeans distinctive from other tribes in Arabia. One of them was their ability as seamen. Where did they learn their seamanship? It may have been in the marshlands of southern Iraq where water transport was easier than land transport. Or it may have been that after repeated conflict with Sennacherib of Assyria, they moved south into Arabia, and developed skills as seamen while they lived on the coasts and in the ports of Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and Oman. Perhaps it was during this time that they visited the ports of Persia and adopted the many Zoroastrian customs that are attributed to them.

Certainly there was trade taking place between Arabian ports and the Indian subcontinent long before the turn of the BC/AD millennium. Perhaps the Nabataeans developed their sailing abilities when they settled along the Red Sea. Whatever the case, they were active as pirates by the time the Egyptian and Greek empires came along.

Diodorus gives an account of Nabataean life in the Sinai Peninsula in II.42.1-5 where he describes the oasis of Feiran, (Biblical Paran as mentioned in Numbers 10:12, 12:16, 13:26, Deuteronomy 1:1, 33:2). This oasis is near the Red Sea, and has a palm grove and a large Egyptian shrine. The Nabataeans were preceded in this area by the Lihyanites, who later became their allies. At the Nabataean city of Egra there is an inscription written in Nabataean stating Mas’udu king of Lihyan. The oasis of Feiran and accompanying gulf were probably known as the Laeanites Gulf during the time that the Nabataeans lived there.

Diodorus tells us:

“After one has sailed past this country, the Laeanites Gulf comes next, about which are many inhabited villages of Arabs who are known as Nabataeans. This tribe occupies a large part of the coast and not a little of the country which stretches inland, and it has a people beyond telling and flocks and herds in multitude beyond belief. Now in ancient times these men observed justice and were content with the food which they received from their flocks, but later, after the kings of Alexandria had made the ways of the sea navigable for their merchants, these Arabs not only attacked the shipwrecked, but fitting out pirate ships and preyed upon the voyagers, imitating in their practice the savage and lawless ways of the Tauri of the Pontusl. Some time afterwards, however, they were caught on the high seas by some quadriremes and punished as they deserved.” (III.43.4)

Quadriremes (galleys with four banks of oars) were ships powered by both oars and a sail. They came into common use before 300 BC, which probably means that the Nabataeans were actively sailing ships and carrying on piracy before this time. (Quinqueremes or galleys of five came into being around 300 BC.) Diodorus also mentions that this extended from the time that the kings of Alexandria made the sea navigable for their merchants. Since the Nabataeans conducted themselves as pirates on the Red Sea, this most likely refers to the building of seaports along the Egyptian coast. This also points to the period stemming from 300 BC, soon after the Greek rulers set up the Ptolemaic kingdom in Alexandria. For example, the seaport of Berenike (Berenice) was the southernmost and most active Egyptian Red Sea port during Hellenistic and Roman times. It was founded by Ptolemy II Philadelphos early in his reign (around 283 B.C.), who named it after his mother. It seems that once this port was built and functioning, the Nabataeans took up piracy, and preyed on the ships sailing the Red Sea and using this port. Later, around 250 BC, as the Nabataeans started to become the principle power in the lands left empty by the Edomites, they established Selah as their capital and Aila (modern day Aqaba) as their sea port. From here, the Nabataeans continued to move on, this time to the Mediterranean coast where they set themselves up in the port city of Gaza. From these two ports they could effectively pirate both the Red Sea and the Mediterranean Sea.

The first century BC Greek historian, Diodorus of Sicily, tells us that the Nabataeans, “… lead a life of brigandage and overrunning a large part of the neighboring territory they pillage it. Some had penetrated to the Mediterranean coast where they indulged in piracy, profitably attacking the merchant ships of Ptolemaic Egypt.” (Diodorus, Book II 48.2)

From these accounts we can conclude that the Nabataeans were equally at home on the seas as they were in the desert. However, not only did they engage in piracy, they also engaged in merchant trade which was considered near-piracy by those buying and selling to merchants.

Early Travels and Trade

Some people are surprised at the thought of early sea trade by the Arabs, but around 510 BC Darius the Great, king of Persia, sent one of his officers, Scylax of Caria, to explore the Indus. Scylax traveled overland to the Kabul River. Having reached the Indus he then followed it to the sea. From there he sailed westward, and, passing by the Persian Gulf, which was already well known, explored the Red Sea, finally arriving at Arsino’, near modern Suez.

Another early historian, Herodotus, wrote of Necho II, king of Egypt in the late 7th and early 6th centuries BC, that “when he stopped digging the canal … from the Nile to the Arabian Gulf … sent forth Phoenician men in ships ordering them to sail back by the Pillars of Hercules.” According to the story, they did this in three years. Upon their return, “they told things … unbelievable to me,” says Herodotus, “namely that in sailing round Libya they had the sun on the right hand.” Whatever he thought of the story of the sun, Herodotus was inclined to believe in the voyage in his comment: “Libya, that is Africa, shows that it has sea all round except the part that borders on Asia.”

Strabo records another story with the same theme. One man named Eudoxus, returning from a voyage to India about 108 BC, was blown far to the south of Cape Guardafui in Africa. When he landed he found a wooden prow with a horse carved on it, and he was told by the Africans that it came from a wrecked ship of men from the west. The greater part of the campaigns of the famous conqueror Alexander the Great were military exploratory journeys. The earlier expeditions through Babylonia and Persia were through regions already familiar to the Greeks, but the later ones, through the enormous tract of land from the south of the Caspian Sea to the mountains of the Hindu Kush, brought the Greeks a great deal of new geographical knowledge. Alexander and his army crossed the mountains to the Indus Valley and then made a westward march from the lower Indus to Susa through the desolate country along the southern edge of the Iranian plateau. Nearchus, his admiral, in command of the naval forces of the expedition, waited for the favorable monsoon and then sailed from the mouth of the Indus to the mouth of the Euphrates, exploring the northern coast of the Persian Gulf on his way.

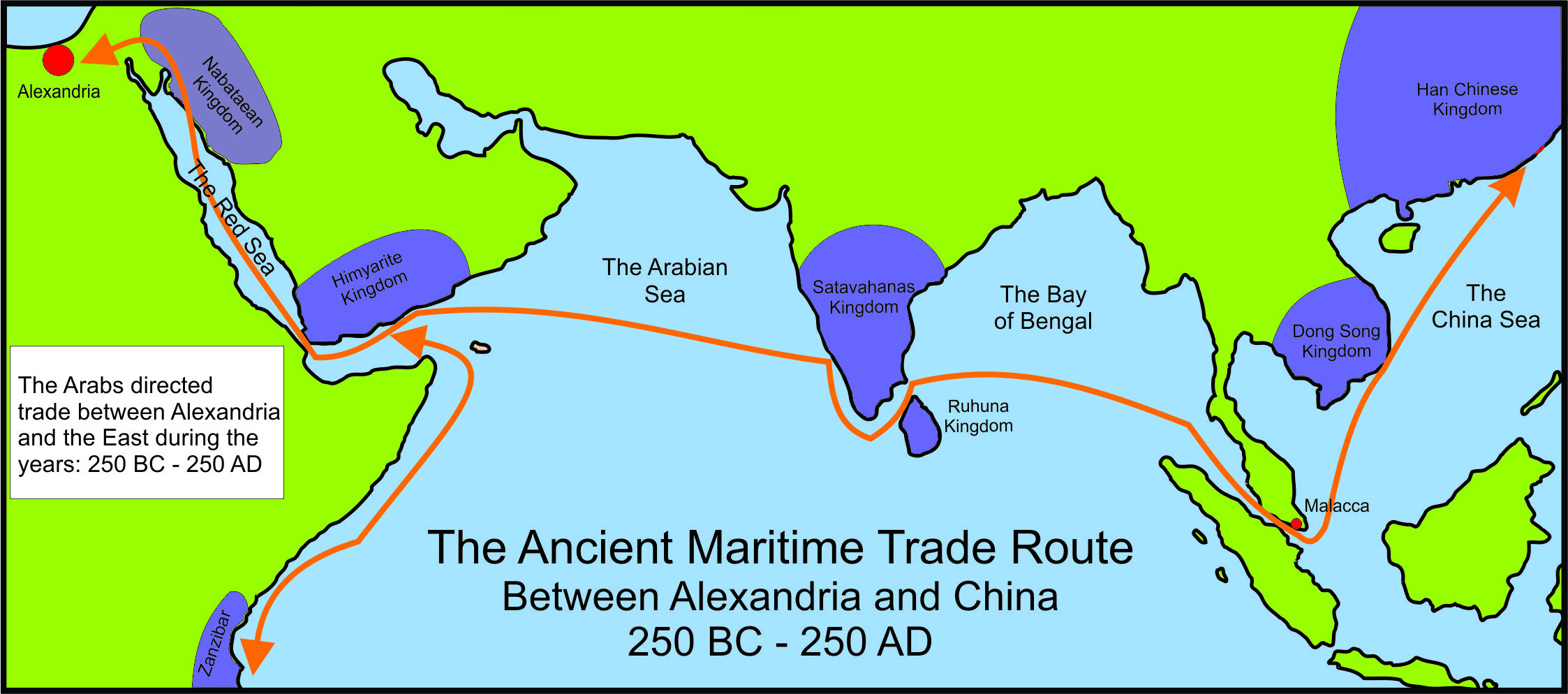

During the time of the Ptolemies of Egypt, Nabataean merchants regularly brought eastern goods to the various Egyptian ports on the Red Sea. These goods then made their way to Alexandria, allowing the city to become the world’s greatest center of trade.

The Periplus Maris Erythraei is an ancient manual for merchants traveling to India. It was written in the second half of the 1st century A.D. by a man with a Greek name, living in Alexandria. This manual is very important as it shows us to what extend the shipping lanes had gained in importance at the expense of the overland caravan routes, and provides us with details about ancient cargoes and ports.

As the coasts became well known, the seasonal character of the monsoon winds was skillfully used. The southwest monsoon was long known as Hippalus, named for a sailor who was credited with being the first to sail with it direct from the Gulf of Aden to the coast of the Indian peninsula. During the reign of the Roman emperor Hadrian in the 2nd century AD, traders reached Siam (now Thailand), Cambodia, Sumatra, Java, and a few seem to have penetrated northward to the coast of China. In AD 161, according to Chinese records, an “embassy” came from the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius to the emperor Huan-ti, bearing goods that Huan-ti gratefully received as “tribute.”

Were these Romans or Nabataean traders acting “in the name of Rome?” It is interesting to note that Ptolemy, the Roman geographer, did not know of these voyages, and on his maps he brought the peninsula of Colmorgo (Malay) southwestward to join the eastward trend of the coast of Africa, thus creating a closed Indian Ocean. He presumably did not believe the story of the circumnavigation of Africa by earlier explorers, and did not know of sailors arriving in China in the name of Rome.

The Arabs were very successful in dominating the eastern sea routes from the 1st century BC to the 15th century AD. A collection of Arabian tales called The Thousand and One Nights recounts the daring exploits of Sinbad the Sailor. Behind the fiction the knowledge of these adventurous Arab sailors and traders can be found, as the stories supply us with detail to fill in the outline of the geography of the Indian Ocean. Regarding the Nabataeans of this time, it is interesting to notice that the historian

Strabo mentions that the Nabataeans “are not very good warriors on land, rather being hucksters and merchants, not like their fighting at sea.” One can infer from Strabo that the Nabataeans were known for their seamanship and piracy, but their land-based military was rather poor. Later, Josephus gives us the story of Cleopatra and Antony’s foiled escape. After their defeat by Octavian (soon known as Augustus) at Actium in 31 BC, Antony and Cleopatra tried to escape on the Red Sea, but their fleet of 60 ships was caught by the Nabataeans and destroyed. This left the Nabataeans again masters of the seas, and Cleopatra and Antony ended their lives by suicide.

The Development of Ship Design

Using the development of ship building in Europe, Arabia, and China we can begin to grasp the effectiveness of the Nabataean merchant marine as well as the tremendous distances they traveled in order to obtain their goods. Most of us are familiar with ships from a European perspective. Many of the books available today give only the European side of shipbuilding. Therefore, we will start there.

European Sailing Ships

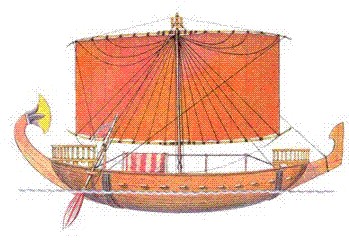

The traditional form of sea-going travel on the Mediterranean Sea involved the combination of the square sail and rowing. The square sail was used with little modification from Egyptian times throughout the Roman Empire and on to the time of the Viking long boats. When the Nabataeans showed up on the Mediterranean Sea with their Arab boats, the Romans took immediate notice. Arab pirate boats sailing out of Gaza could make better use of the wind, and in many situations out-sailed the slower Roman boats. This triangular sail was most likely developed on the Red Sea where strong winds often blew from the wrong direction for sailors.

The traditional square sail of Rome and India was severely hampered in these conditions, and it seems that on the Red Sea the triangular sail quickly replaced it. Soon the Romans began to adopt the use of the Arab sail pattern, and eventually the Vikings in the north of Europe called the triangular Arab sail the “lateen” or Latin form of sail.

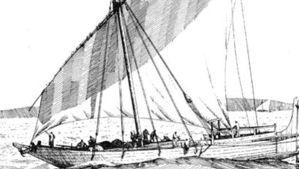

The lateen sail was a triangular sail that was affixed to a long yard or crossbar, mounted at its middle to the top of the mast, and angled to extend aft far above the mast and forward, down nearly to the deck. The sail, with its free corner secured near the stern, was capable of taking the wind on either side. The lateen sail enabled the vessel to tack into the wind, immensely increasing the potential of the sailing ship by allowing the ship to sail close to the wind. Then, sometime around the turn of the millennium, shipbuilders in China started using the sternpost rudder. No one knows who invented it, but soon after this, Arab shipbuilders adopted this invention onto their Dhows. This allowed the Dhow to have greatly increased maneuverability, as it allowed them to take full advantage of their improved sail power in tacking into a contrary wind.

This was followed by the introduction of the magnetic compass, originally invented in China around 200 - 300 BC. The compass provided a means of checking navigation on the open seas in any weather. Arab sailors had all three of these advantages as they developed their knack for sailing during the five hundred years that the Nabataeans dominated the seaways. Later, as the Nabataean empire waned, the Arabs of south Yemen and Oman took their place as maritime traders between Asia and Europe.

Another important skill was navigation by the stars. A few decades ago, those who suggested that astronomy had reached an advanced state, long before the invention of the telescope, were generally ridiculed, or ignored. But in the past few decades, evidence has mounted overwhelmingly. Many scholars now accept that the procession of the equinoxes (supposedly discovered by the Greeks) was actually known, in pre-Dynastic Egyptian times. A systematic kind of astronomical observation began in very early times.

The most ancient astronomical texts presently known are dated from the Egyptian Ninth Dynasty (2150 BC). These texts are called ‘diagonal calendar’s or ‘diagonal star clocks’. They give the names of the thirty-six decans, or stars which rose at ten-day intervals at the same time as the sun. More elaborate star charts were found in the New Kingdom on the ceiling of the tomb of Senenmut, Queen Hatshepsut’s architect, and on the ceiling of the temple of Abydos. In the tombs of Ramesses IV, VII, and IX, inscriptions which relate to the first and the sixteenth day of each month, give the position occupied by a star at each of the twelve hours of the night in relation to a seated figure.

Using their knowledge of astronomy and the equinoxes, sea-going Arab sailors could navigate their way across the Indian Ocean by the stars, rather than following the coastline.

It would not be until later, towards the end of the Middle Ages, that Europeans would combine these improvements into their sea going vessels. Then, with better equipment, such as barrels for carrying water, more reliable ropes, sails, anchors, the availability of navigational charts, (first recorded in use on board European ships in 1270), and with the astrolabe for measuring the angle of the Sun or a star above the horizon, the adventurous European mariners could make voyages of discovery that would mark the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the expansion of Europe westward across the Atlantic Ocean.

Roman Transport Ship

Chinese Sailing Ships

Water transport played an important role in the history of China, which had vast land areas and poor road communication systems. Starting with a dugout canoe, the Chinese joined two canoes with planking, forming a square punt, or raft. Next, the side, the bow, and the stern were built up with planking to form a large, flat-bottomed wooden box. The bow was sharpened with a wedge-shaped addition below the waterline. At the stern, instead of merely hanging a steering oar over one side as did the western ships, Chinese shipbuilders contrived a watertight box extending through the deck and bottom that allowed the steering oar or rudder to be placed on the centerline thus giving better control.

The stern was built to a high, small platform at the stern deck, later called a castle in the West, so that waves from the rear could not spray into the ship. Thus, in spite of what to Western eyes seemed an ungainly figure, the Chinese boats, called junks, were excellent for sea travel as well as for beaching in shallow water. The principal advantage, however, not apparent from an external view, was the junk’s great structural rigidity. In order to support the side and the bow planking, the Chinese used solid planked walls (bulkheads), running both longitudinally and transversely thus dividing the ship into 12 or more compartments, producing not only strength but also protection against damage.

In rigging, the Chinese junk was far ahead of Western ships, with sails made of narrow panels, each tied to a sheet (line) at each end so that the force of the wind could be taken in many lines rather than on the mast alone. In addition, the sail could be hauled about to permit the ship to sail somewhat into the wind.

Once the Chinese had sea-going junks, they readily sailed throughout the islands of the Far East doing trade. Evidence is now being uncovered that demonstrates that the Chinese reached India during the time of the Roman Empire. It is now accepted that the port of Palk Bay at the northern tip of Sri Lanka was the meeting place where Chinese boats would unload their cargoes and Arab traders would buy them for transport back to Arabia.

Egyptian Ships

Since water navigation down the Nile was the principal means of transport for Egypt, the Egyptians also built a whole range of practical boats, well adapted to different uses and geography and climate.

Egyptian ships varied enormously in size. Some of them were huge. The Greek historian Diodorus mentions one, made of cedar, which measured about 450 feet in length. Another boat, this time a military vessel, built on the orders of Ptolemy Philopater, was of the same length, but was 75 feet wide and 100 feet high. According to Diodorus, it could carry four hundred sailors, four thousand oarsmen, and three thousand soldiers. This certainly seems a heavy load, besides which the passengers must have been very cramped!

There were some very large freighters as well. These were used for transporting grain, stone, bricks, and even the gigantic obelisks, which were hewn out of a single block in the quarries of Aswan, and then carried on the river to the site of the temple, where they were triumphantly erected. A single statue of 1,000 tons was quarried in Aswan, transported several miles from the quarry to the river, lifted onto a boat, and ferried for one hundred and fifty miles, off-loaded, transported several miles to the temple, and finally erected onsite.

Egypt had a strong and formidable navy to protect its shores and its trade routes on the Mediterranean and Red Sea. The sailors of the Royal Navy’s “King’s Ships” were specially trained for the sea. Herodotus and Diodorus both mentioned these ships of war, which were fitted out by Sesostris on the Red Sea. There were four hundred King’s Ships altogether, although most of these were on the Nile and along the Mediterranean coast.

As such, trade, and the means of protecting it by ships of war, existed in Egypt, at least as early as the 12th Dynasty, or about two thousand years B.C. These commercial and naval ships were served from several ports, guiding landmarks, water markers, and loading and unloading facilities. Several roads, along with supply stations were provided between the seaports and the populated centers along the Nile.

It was these “King’s Ships” that the Nabataeans challenged and eventually defeated, so that they could monopolize the sea-going trade on the Red Sea and beyond to Asia. The ancient historians seem to indicate that the Egyptian and Roman Navies sailed only in the Red Sea and not beyond. It was the Arab traders, it seems, who traded with India and China during the first one hundred years BC and AD, not the Romans, Greeks, or Egyptians.

The Roman Navy

The Roman Navy has a different story than the Egyptians. Since the earliest times, the Romans had not been known as great seafarers. This they left to the intrepid Phoenicians, Greeks, and later, the Carthaginians. The Romans preferred to fight all of their battles on land, being much more comfortable on solid ground. Over time, however, they learned that their navy must play a vital, if not overly glamorous, role in keeping the Empire safe from various external forces. Their navy saved the Romans during the Punic Wars, brought final victory to Octavian, who would go on to become the first Emperor of Rome, and allowed the Romans to call the Mediterranean ‘Mare Nostrum’ or “Our Sea,” by eventually keeping it free of piracy (including the Nabataeans).

The Romans always maintained a dislike for the sea, yet they remained dependent on it for trade and commerce, and thus were forced into keeping a strong hold on it by keeping up a strong navy.

Chiefly from the accounts of the Greek historian Polybius, we learn that the Roman Senate ordered the construction of 120 warships during the first Punic War (3rd century BC). This was not the beginning of the Roman navy, as small contingents recruited from Magna Graecia had provided a flotilla of small, second-class ships from around 282 BC. It did, however, mark the emergence of Rome as a naval power in the Mediterranean.

The 120 ships were made up of two classes, as Polybius tells us, 20 triremes, and 100 quinqueremes. The former was of the same basic design that had been in use by the Greeks for 500 years, with three levels of oars on each side, the top level containing 31 oars, rowed by one man each and the other two levels containing 27 each.

The second type of ship, the quinquereme, was a new type of ship that would make up the majority of the fleets on both sides of the three Punic Wars. These quinqueremes or “fives,” (Lat. penteres,) represented a major advance over the trireme. Dionysius I, a tyrant of Syracuse in Sicily, is credited with the quinqueremes invention along with that of the oar system that made it possible. Previously, as in triremes, each oar was rowed by one man. Dionysius conceived oars rowed by two or more men. This allowed the construction of “fours,” “fives,” and higher rated ships, although the maximum workable number of oar levels was three. A quinquereme could have three levels of oars, the top two possessing oars rowed by two men each, and the bottom by one. Alternatively, it could have two levels, the top rowed by three men to an oar, the bottom by two. A third option was a single level of oars, each oar worked by five men. It is this third arrangement that benefited the Romans. Each individual oar on the galley had to be worked by at least one trained rower, so that it did not foul the other oars. In this way, the Romans could place four untrained slaves beside one experienced slave and still get reasonable performance.

Roman ship with a crow or raven

The standard tactic of the day was ramming the opponent to put a hole in his side with the bronze encased ram on the prow of every warship. This required a great deal of skill, as the window for a successful ram attack was in the area of eight seconds, and that only if the crew was skilled enough to make last-second corrections, as a vessel arriving early was in danger of being itself rammed by its prey. A second option was to make as if to ram, and then turn away, attempting to shear off the enemy vessel’s oars, immobilizing it.

The standard tactic of the day was ramming the opponent to put a hole in his side with the bronze encased ram on the prow of every warship. This required a great deal of skill, as the window for a successful ram attack was in the area of eight seconds, and that only if the crew was skilled enough to make last-second corrections, as a vessel arriving early was in danger of being itself rammed by its prey. A second option was to make as if to ram, and then turn away, attempting to shear off the enemy vessel’s oars, immobilizing it.

The Romans found, in the course of their first skirmishes with the Carthaginians in the first Punic War, that they lacked the seamanship and necessary skill to outperform the Carthaginians. However, someone in the Roman camp, perhaps from the seafarers of Magna Graecia, came up with a solution that would allow the Romans to benefit from their experience with land warfare. This was the “crow” or “raven,” (Latin corvus,) a 35 foot long bridge mounted on a swivel so that it could be turned and dropped on an adjacent enemy vessel. A large spike at the end of the corvus bit into the other ship, locking the two craft together. Then the Roman marines, who were in a larger proportion to the crew than on Carthaginian ships, would storm across and engage the enemy crew, usually resulting in a Roman victory.

In naval battles, sails were usually taken down, to improve maneuverability and also to reduce the risk of the mast snapping from the impact of ramming. With favorable winds, sometimes the skillful Carthaginians, who fought under full sail, could race by the slower Roman ships and break their blockades of certain ports.

In 247 BC, the Roman treasury was exhausted, so private citizens covered the expenses of 200 new quinqueremes. These were not equipped with the corvus, which was never used again.

The South Arabian Merchant Ships

According to Agatharchides (130 BC), the Sabaeans of southern Arabia (Yemen) made use of rafts and leather boats to transport goods from Ethiopia to Arabia (Photius, Bibliotheque VII). Agatharchides also tells us that the Minaeans, Gerrheans, and others would unload their cargoes at an island off the coast so that Nabataean boats could collect it. In other words, he suggests that although the Sabaeans themselves may have confined their maritime activities to crossing the Red Sea, the Nabataeans in the north had already taken to maritime transport by the second century BC. (Agatharchides 87, and cited by Diodorus Siculus Bibliotheca III 42:5 and by Artemidorus in Strabo Geography xvi, 4:18, as well as Patricia Crone in her book Mecca Trade, Spices of Araby, Classical Spice Trade, Page 23)

The island in question was probably Tiran (Woelk, Agatharchedes p 212). The Nabataeans would have transferred the goods from the Sabaean rafts and leather boats to their own wooden Dhows.

The Nabataean (Arab) Navy

As far as I know, there are few, if any records of the Nabataean navy, either military or merchant. We do, however, have good information about Dhows, as many are still in use to this day.

Long before the Europeans switched to using lateen type sails rather than using rowing galleys, the Arabs became masters of sailing. They had within their grasp, knowledge of astronomy and equinoxes. They were familiar with the fixed rudder, compasses, and the use of triangular sails that could tack with the wind.

Their smaller ships were far more agile and much faster than the Roman or Egyptian rowing galleys. As long as the wind blew, they were masters of the sea. When the wind stopped, however, the rowing galleys could easily catch them and ram them. Diodorus tells us that Egyptian or Greek quadriremes were responsible for sinking several Nabataean pirate ships on the Red Sea.

However, by the time Cleopatra and Mark Antony tried to make their escape to India, the Nabataeans had gained control of the Red Sea. The Egyptian navy was engaged and sixty Egyptian ships were destroyed. (Josephus) After this, the Nabataeans enjoyed a monopoly on sea trade until 106 AD when the Romans annexed them. From this point on, Roman ships also began to sail the Red Sea, but as far as we know, few of them were used for trade with India and China. This was usually done by Arab private enterprises, as we will discover later in this book.

In the paper “Arabia” in ancient history we have explored how the ancient world all considered the Nabataeans to be Arabs, and the Arabs to be Nabataeans. For example, Josephus calls Aretas the king of the Arabs. We have also prepared a series of papers that examine the maritime advancements of the various Arab groups in the first two centuries BC, pointing out that from all of the Arab groups of that time, it was only the Nabataeans who had the nautical ability to sail to India and Ceylon. (See Who were the Ancient Arab Sea Traders)

Picture copyright held by their respective owner

Page Discussion

Membership is required to comment. Membership is free of charge and available to everyone over the age of 16. Just click SignUp, or make a comment below. You will need a user name and a password. The system will automatically send a code to your email address. It should arrive in a few minutes. Enter the code, and you are finished.

Members who post adverts or use inappropriate language or make disrespectful comments will have their membership removed and be barred from the site. By becoming a member you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy, Cookies & Ad Policies. Remember that we will never, under any circumstances, sell or give your email address or private information to anyone unless required by law. Please keep your comments on topic. Thanks!