Text copyright Canbooks.

Picture copyright is held by their perspective owners

Introduction

In this short paper I would like to outline the basic skills that were necessary for sailing in ancient days. First I will compare the use of the square sail and the lateen sail, and end with a look at the various techniques that were used by the ancient Arabs for navigation, both in the desert and on the sea.

Square Rigged Ships

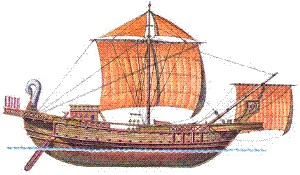

In the ancient world the square sail was employed universally in the Mediterranean on the seagoing ships of the Egyptians, Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans. In Hellenistic and Roman times a spritsail was sometimes set on a small raking foremast, known as an artemoon, in order to sail with a beam wind. This was a valuable device, but it was still a square sail. Northern Europe only knew of the square rig until late in the Middle Ages. They were the farthest from Arab influence, and the Vikings of Scandinavia continued using the square sail, long after those on the Mediterranean had started incorporating the advantages of using triangular sails on their ships.

A square rigged Roman trade ship

In India square sails are depicted on coins of the Pallava dynasty (coeval with the Sassanids) and in the Ajanta ship of the seventh century AD.) (Elliot, W., Coins of Southern India, London 1885) An indication that lateens are not native to India is found in their absence today in inland water regions remote from foreign influences.

Ajanta ship

Square rigged sails had the advantage of providing stability on large ships and in heavy seas, and they remained the main type of sail on European vessels until the last days of sail. However, the lateen sail provided greater maneuverability and ability to tack on rivers and in narrow waters. The fore-and-aft sail had an advantage in that it can keep much closer to the wind.

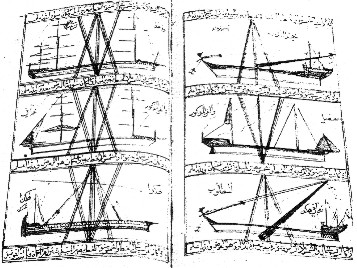

Triangular Rigged Ships

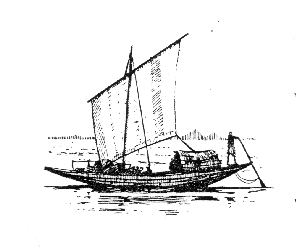

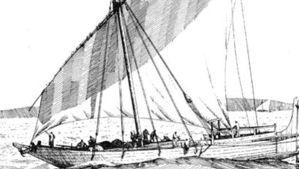

The triangular sail was known as the lateen sail, and has been used in Arab ships from Morocco to Indian, the Persian Gulf to Mozambique. This sail is triangular in shape attached fore and aft, and is very tall and high peaked. In the Indian Ocean the fore angle of the sail was cut off to form a luff. This shape may have been the third of four stages of the evolution of lateen sail.

Apparently most very ancient ships simply used square sails. In time however, the square sail was attached fore and aft, and was tilted down at the fore end. This made a balance-lug. There are drawings of ships of this type from ancient Egypt, showing ships sailing downstream on the Nile against the prevailing north wind. A modern version of this is found in the Sudanese naggar-lug, and in the balanced lugs of Indonesia. These first appeared on bas-reliefs of Boro-Budur in Java, which date from the tenth century. The Javanese proa which survived until recently has a similar style; the sail is much broader than high.

From the balanced-lug it was a natural development to shorten the fore-portion of the sail and raise the back in order to catch more wind. This would have produced the type of lateen sail that is found in the western half on the Indian Ocean.

Maritime historians have often argued over where this sail was developed and how its use may have spread.

There are three possible scenarios. First it may have developed in the Mediterranean, and spread toward the Indian Ocean, or it may have developed in the Indian Ocean and spread towards the Mediterranean. Each of these scenarios has its supporters and it’s problems. A third scenario, which seems more likely, is that the lateen sail was developed on the Red Sea.

There are several things that seem to point in this direction. First, the square sail was obviously the sail of choice in the Mediterranean and in the Far East. These areas of the world contained vast seas that were easily crossed using square sails. The Red Sea, and particularly the Gulf of Aqaba on the other hand were constantly exposed to contrary winds. In order to sail on these seas, sailors had to constantly battle winds that blew against them. In this sort of setting the lateen sail was at its best.

Secondly, the earliest evidence of the existence of lateens on the Mediterranean is in Greek Byzantine manuscripts of the late ninth century which show drawings of lateens. Before this, in antiquity, only the square sail was found in this sea. This would lead us to suspect that the lateen came to the Mediterranean in the wake of the Arab expansion. (Bibliotheque Nationale, MS, grec., no. 510, fols. 3 and 367v,; H.H. Brindley, Early Pictures of Lateen Sails” in Mariner’s Mirror col. xxi, 1926) (Sottas, J., An Early Lateen Sail in the Mediterranean, in Mariner’s Mirror, 1939)

Third, the Italian name mezzana, with it’s French offspring misaine, and English mizzen are derivatives of the Arab word miizaan, meaning balance. These mizzen masts that were found on Italian ships of the later Middle Ages, could have had it’s name borrowed from the Arabic miizaan because it was a supplementary mast balancing the main mast. On the other hand, other scholars have pointed out that the name mezzana mast could have come from the Latin mediana, which means ‘middle.’

It is interesting to notice that in the north of Europe, during the 1400’s, ships were only square rigged and were entirely dependent on a fair wind. They were quite unstable, and were never used to attempt to make headway against an adverse wind and thus were unable to make long journeys to cross oceans.

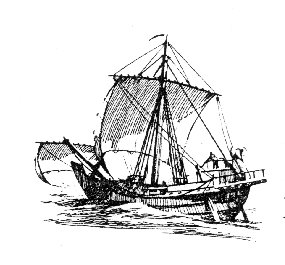

Then suddenly in the 1500s, lateen sails burst on the scene, and ships developed into three masters with square sails complimented by lateen mizzens. These ships were capable of making long ocean voyages and were used by Columbus, Diaz and Vasco da Gama.

Lastly, it seems that during the Byzantine era, the forepart of the lateen sail was changed to a point, making it a complete triangle. This occurred first in the Mediterranean, but the Arabs of the Red Sea and Indian Ocean kept their old form. The lateen eventually reached North European waters at the end of the Middle Ages, and there developed into every sort of fore-and aft rig.

Likewise, the lateen sail seems to have made its way from the Indian Ocean towards the seas of far south Asia. Since there are drawings from India, which demonstrate the use of the square sail there, and since the Chinese rigged their junks with square sails, it is safe to assume that the lateen sail was an Arab invention that most likely developed on the Red Sea.

The Development of the Lateen Sail

The square sail was employed almost universally in the ancient world. It was only during the early Byzantine period in the eastern Mediterranean that any evidence emerges that triangular sails began to appear on the Mediterranean Sea.

The square sail, though stable on heavy seas, is not very versatile to make much use of any headwinds. Square sails were still used until very recently on the sewn sambugs of Aden as well as lateen sails.

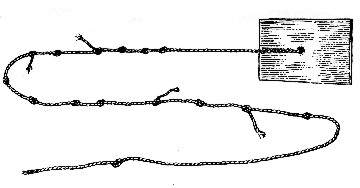

The Lug Sail

Many efforts must have been made to make the square sail better for sailing close to the wind, so it could utilize a head-wind. The simplest way was to set a square sail fore and aft, tilting it downwards at the fore end to make a balance lug illustrated here.

The Arab Lateen or Settee Sail

From the lugsail it was an east step to shorten the luff (fore part) and heighten the sail aft to lengthen the leech, in order to catch more wind. The Arab lateen or more correctly, the settee sail is a very effective fore-and-aft rig. It was developed in Arab waters well before the coming of Islam, and may have been the type of sailing ship that the Nabataeans would have used to sail on the difficult waters of the Red Sea.

A full description of the dhow with its settee sail is included in the paper The Dhow.

The Fully Developed Lateen

The final step was taken on the Mediterranean before 900 AD, turning the Arab sail into a triangular sail. This type of sail was used on the Mediterranean for small boats for many years.

Sailing Techniques

Sailing Close to the Wind

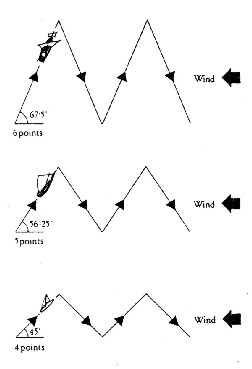

- The square sail on a keeled ship, (for example a Greco Roman merchantman) can give an angle of 671⁄2 (6 points) to the line of the wind when fully trimmed and tacking into the wind. The keel provides resistance to the sideward force of the wind.

- A square rig with the help of some fore-and-aft lateen (mizzen) sails as used on European sailing ships from the 15th century to the 19th century allows a 56 1⁄4 (5 points) to be obtained. An Arab lateen rig gives the same angle when close-hauled but since a greater area of sail catches the wind, it sails more swiftly and efficiently.

- A well-designed Arab lateen could come within 4 points of the wind. One can see why Nabataean and other Arab sailors would desire such a boat for pirate activity against the Greeks and Romans.

- The most efficient design of sail for utilizing a head wind is the complete fore-and-aft rig of a modern yacht. It can usually come within 4 points of the wind, and sometimes even achieves 3.

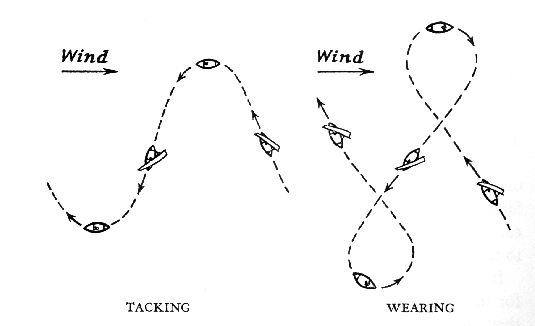

Tacking and Wearing Around

The methods of sailing an ancient dhow must have been much like those today, since the rig was much the same. In sailing with the wind the Arab lateen functions exactly as a square sail. When steering a course into the wind, the dhow would prefer to ear around, that is, to change tacks by going round stern to wind. Tacking involves bringing the bow around into the wind, and since Arab vessels were built with small rudders it was difficult or impossible to bring the bow across the wind, if the wind was strong. Wearing around means losing way, but it is easier, to wear is to take the line of less resistance. When wearing, as when tacking, the yard must be transferred to the other side of the mast; but when wearing the wind aids this maneuver, whereas when tacking the wind tends to hinder it.

There was no reefing of sails in a strong wind, but the yard could be lowered, as today, and it is probably that a spare yard and sail of smaller size were carried, as in the vessels seen by Colomb in the nineteenth Century. (Colomb, Slave-catching, pp 36-38; Mas’uud Muruj, volume I, page 234, “The great sail”; Muzurg, pp 44-47, 87-88, 16568, ibn-Battutah, vol ic, pp. 185-186)

Navigation

In my paper, Were the Nabataeans Really Sea Going? I demonstrate how the Nabataean people took to sailing ships. The speed at which they did this might be considered remarkable, if it were not for the fact that navigating in a featureless desert is very similar to navigating on a featureless ocean. Therefore, before the Arabs became seamen they were knowledgeable in navigation skills. In the section below, I will demonstrate the basics of this navigation, whether it be used on the high seas, or in the depth of the Arabian desert.

However, not all Arab tribes knew how to navigate by the stars. Indeed, only a very few had this skill, as even today only the Slayb tribe are known as the trackers and guides in the desert. (See: Where are the Nabataeans Today?) Many early sailors sailed along the coast, always keeping land in site. In this way, they simply harbor-hoped along the coast. One wonders what sea captain would have committed himself to the emptiness of the open sea without a knowledge of navigation by the stars. It would seem a small step however, for desert traveling Nabataean merchants to move on to being ocean traveling merchants, if they had the occasion to own ships and the need to transport goods by them.

Modern navigation includes three aspects. Finding latitude, longitude and accurate time-keeping. By knowing one’s location and the speed of their travel a person can accurately navigate across featureless landscapes.

qiyas

Before the invention of the compass, watch, and the sextant, the mariner’s main guide was latitude. To obtain their latitude, Arabs measured the altitude above the horizon to a known star, and then deduced from this the altitude of the Pole Star, (since the Pole Star was the one star that did not move in the sky). In some cases ancient navigators measured directly the altitude of the Pole Star. This was the simplest method, and was known as the science of qiyas. The easiest method was to use the width of a finger. When held at arm’s length, the width of four fingers was considered to measure 4 isba’. In a 360 degree circle there were 224 isba’. It was considered that a day’s sailing due north would raise the Pole Star 1 isba’ from the horizon. For those traveling on land, the isba’ was further divided into 8 zam. Thus land distances were often measured in zams.

kamal

A more accurate, but still simple instrument was known as a kamal. This was a small parallelogram of horn or wood measuring about one by two inches with a string inserted in the center. On the string were nine knots at measured intervals.

The end of the string was held in the teeth. The lower edge of the horn was placed on the horizon while the horn was moved along the string until the upper edge touched the required star. The knot at which the horn covered the exact distance signified a certain number of isba’ of altitude of the star. The altitude of the Pole Star could then be deduced from the rahmani.

An alternative way of using a kamal was to move the knots through the teeth until the piece of horn or wood covered the required star altitude.

Vasco da Gama’s pilot from Malindi used a kamal, and the Portuguese adopted it and eventually modified the spacing of the knots to measure degrees.

Sometimes Arab and Indian seamen added extra knots marking the latitudes of particular ports of call, or they simply used a kamal on which all the knots indicated particular ports of call.

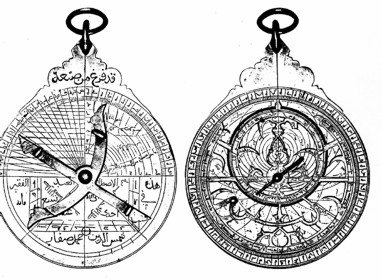

astrolabe

The astrolabe was developed at a slightly later period. It was a chart was based on the rising and setting of fifteen fixed stars. Later astrolabes also included the addition of North and South. This method probably pre-dated the introduction of the magnetic compass. However, when used on the compass, each star name division came to signify one rhumb or 1⁄32 division of the compass.

The astrolabe was also known as a windrose, and traditionally it had many Persian names for stars. (eg. qutb al-gaah, mutla’ al-silbaar, khaan (rhumb) etc., which the Arabs must have taken from a Persian windrose. However, many other names are Arabic and in some cases an older Arabic name was displaced by a Persian one. Eg. The Ursa Minor constellation (Ursa Minor and Major) was banaat na’sh before it became qutb al-gaah.

On the astrolabe, latitude was determined by the height of the sun or the pole star, which was measured by the qiyas figure system. Astrolabes were quite difficult to use at sea because of the rolling of the ships, which made it hard to determine the vertical line accurately. However, they could be used on shore, and the latitude of every port and headland must have been recorded in the books of nautical instruction or rahmaanis.

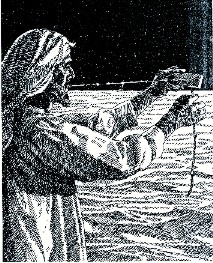

Sun locations

Another very simple navigation method that was used by many early dhow captains was simply the position of the sun or North Star above the boat. By standing on various locations on the boat, they could place the sun or North Star above, right, left or behind the dhow. As long as they kept the stars at a correct position above the rigging they were assured that they would arrive at their destination.

Nautical Manuals

Beside astronomical tables, charts, and latitudes, the rahmaani or nautical manuals contained information about winds, coasts, reefs, and everything that a captain would need to know. Some of these manual became very popular, such as Kitab Ma’din al-asrar fi ‘ilm al-bihar (The Mine of Secrets in the Science of the Seas) by Shaikh Nasr bin ‘Ali al’Haduri. This book contains latitude and longitude tables as well as drawings of the position of the sun above the dhow. (above)

Compass

The magnetic needle was known in China from ancient times, but there is little mention of it being used as a nautical instrument before the tenth century. It is likely that the compass was not considered very important in the east, as the skies over the Indian Ocean were usually very clear, especially during the times that the Arab sailors traveled with the monsoons. It was only under the clouds of the North that it was eagerly made use of.

A Chinese spoon compass. A spoon shaped piece of magnetic stone, called a loadstone was placed on a polished bronze board. The spoon turned until it pointed to the North Pole. On the right is an ancient Arabic compass chart

Sextant

During the 17th century, with the invention of timekeeping instruments, the sextant became much more common as the main instrument for calculating position and speed.

Birds

Shore sighting pigeons were also employed in some parts of the Indian Ocean. Pliney mentions them as used by the Singhalese in the first century AD because they had no nautical astronomy. A Chinese source of the ninth century refers to them on Persian ships.

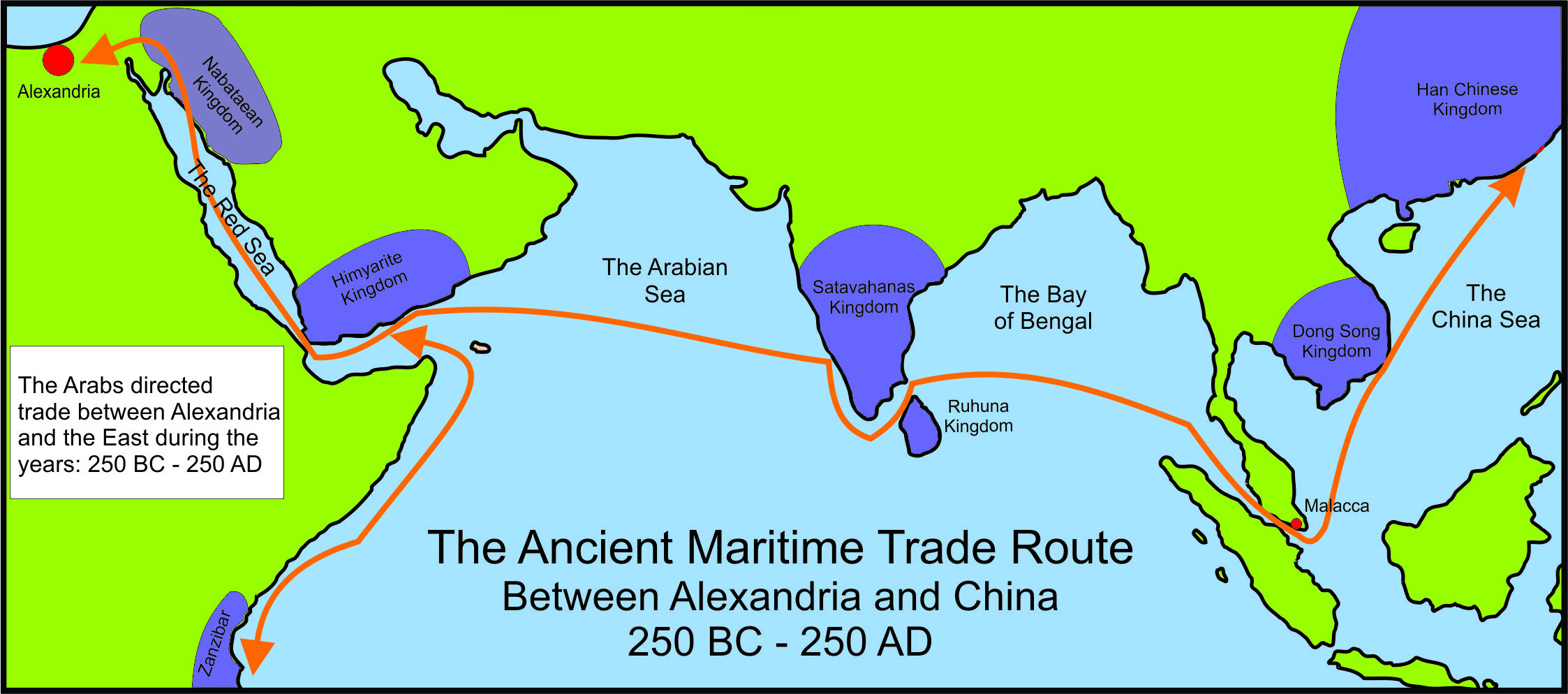

The Trip To India and China

From ancient times ships crossed the Indian Ocean from Arabia to return laden with exotic goods that would bring exorbitant prices in the bazaars and markets of the Middle East. On land the Silk Road was fraught with hazards. Hostile governments, highwaymen and natural disasters awaited those who attempted the long and difficult road between China, India and Europe. That road crossed some of the highest mountains in the world, not to mention some of the most hostile deserts. It required the merchant to pass through many fiefdoms and kingdoms where local lords demanded at least some token tax on the goods that passed through their lands. On top of this, pack animals required fodder and regular rest.

The maritime route to India and China also had its difficulties, but once the ancient Arabs understood them, they could be quite easily passed. The knowledgeable sea captain sailed straight down the middle of the Red Sea, avoiding the pirates that lurked along the shore. He then took on water and supplies in South Arabia and then made straight across the Indian Ocean for India. Using various navigational aids, and a knowledge of the monsoon winds, the industrious Arabs could make a return trip in 18 months to two years.

The advantage that the sea captain had, was that a small crew of ten men and a boat could return laden with twenty to fifty tons of cargo, and they could transport it right up the Red Sea within a few hours caravan journey from Alexandria. Then from Alexandria the merchants on the Mediterranean could carry the cargo of exotic goods to the ports of Greece and Italy where it would be snapped up by the wealthy families of the Roman Empire.

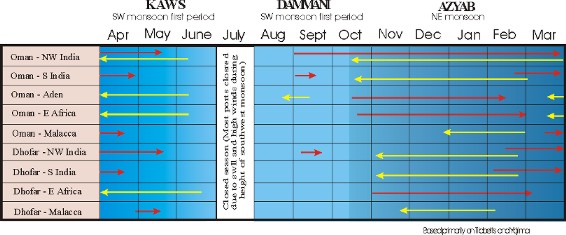

The Monsoons

From an Arab perspective there are three basic monsoon winds. First of all, from April to June, the Kaws wind blows southwest. Later the Dammani SW monsoon blows from August to the middle of October. At this time, the monsoon changes direction, and the Azyab monsoon blows in a NE direction.

Most ships crossing the Indian Ocean planned to leave the east coast of Arabia during the second half of November and the first half of December. Ships leaving the Red Sea would start out the middle of October, so that they could catch the Ayab monsoon across the Indian Ocean, directly to the Malabar cost, reaching Kulam Mali during December. If they were moving on to China they would have to wait for the cyclones of the Azyab to die down in the Bay of Bengal before journeying on in January, crossing from Mulam Mali round the south of India to Kalah Bar in the Malay Peninsula. Arab ships usually did not venture farther than this, as Chinese junks brought their trade goods to the Malay Peninsula, and may to the island of Ceylon. (Sri Lanka) Once the Kaws winds started to blow, the Arab sailors would start for home, laden with their goods.

The chart below illustrates some of the sailing seasons that existed between India, Arabia and Africa. As local conditions such as land breezes would vary along the Arabian coast, the seasons were more complicated for the specific ports shown in the chart. Nevertheless the chart provides a broad outline.

From the table you will notice that the south-west monsoon strikes earlier further south, and lasts longer. As it moves northwards its duration shortens. Hence the Malabar coast of India is a dangerous place to be as early as May and remains so through September. This means that the sailing season in Malabar, India was only seven to eight months long. This affected the Indian vessels more than the Arab ones, for while the Indians must be all the way home before May, Arab vessels must only be clear of the Malabari waters before then. This allowed the Arabs more time to travel since they had a much longer sailing season when traveling from Arabia to India and back. This would help explain why the Arabs, who came from a land without abundant timber, dominated Indian Ocean trade routes for long periods.

Nabataeans and Sea Navigation

Very few Arab tribes knew now to navigate by use of the stars. Ibn Wahsiyah makes it plain to us that this knowledge was known to the Nabataeans from of old. If this were true, then it would have been a small step for the Nabataeans to have adopted their land based navigational skills to the sea.

As mentioned earlier, most sea captains, who had only every traveled along the coast, would never cast off and try and sail across the empty sea. However, if the Nabataeans had visited India and or China via the land route (Petra, known to the Nabataeans as Rekem was recorded in the records of Chang Ch’ien, special envoy to the Chinese Emperor Wu-ti 138-122 BC. It is assumed that Nabataean jugglers and entertainers returned with Chang Ch’ien to China) then they could have produced rough charts of the locations of these countries. This would have given the Nabataeans the knowledge they needed to sail directly across the Indian Ocean from Arabia to India. Is this speculation? More information and proofs are presented in the paper “Who were the ancient Arabs who traded with India?”.

Now you can learn more about the ancient Nabataean trade routes. Discover the people and civilization that used the dhow to explore the world!

Bibliography

Anderson, C., R and R Anderson, The Sailing Ship, London 1926

Argyle, E. W., The Ancient Dhow, Sea Breezes, XVIII, 1954

Barlow E. W. _Currents in the Persian Gulf, Northern Portion of the Arabian Sea and Bay of Benga_l, Marine Obs. 1932

Boughet, Michael, R. and N. Lishman, Ships of Muscat, MM 44, 1958

Bowen, R. Le Baron, Arab Dhows of Eastern Arabia, Rehoboth, Massachusetts, 1949

Bowen, R. Le Baron, The Dhow Sailor, American Neptune II, 1951

Bowen, R. Le Baron, Marine Industries of Eastern Arabia, Geographical Review 41, 1951

Bowen, R. Le Baron, Primitive Watercraft in Arabia, American Neptune 12, 1952

Bowen, R. Le Baron, Maritime Superstitions of the Arabs, American Neptune 15, 1955

Bowen, R. Le Baron, The Earliest Lateen Sail, MM 42, 1956

Bowen, R. Le Baron, Fore-and-aft sails in the Ancient World, MM 43, 1957

Bowen, R. Le Baron, Early Arab Ships and Rudders, MM49, 1963

Bowen, R. Le Baron, Early Arab Rudders, MM 52, 1966

Casson, L. Ships and Seafaring in Ancient Times, 1994 160 pp.

Casson, L, The Ancient Mariners: Seafarers and Sea Fighters of the Mediterranean in Ancient Times. (Second Edition) 1991, 299 pp.

Casson, Lionel, Fore-and-aft Sails in the Ancient World, MM42, 1956

Chatterton, E. K., Fore and Aft Craft and their Story, London 1927

Chetham, Michael, Dhows in East Africa, Country Life 108, 1950 PP 1803-7

Clowes, G.S.L., Sailing Ships, London 1932,

Clowes, G.S. L., The Story of Sail, London, 1936

De Graeve, Marie-Christine, The Ships of the Ancient Near East (2000-500BC), Department Orientalistiek, Leuven, 1981

Delgado, James P. (ed) Encyclopedia of Underwater and Maritime Archaeology

Dimmock, L., The Lateen Rig, MM 32, 1946

England, B., The Kamal, MM 41, 1955

Elliot, W., Coins of Southern India, London 1885

Fox Smith, C., Arab Craft, MM 28, 1942

Gabrielsen, Vincent, The Naval Aristocracy of Hellenistic Rhodes, David Brown Book Company, 1997, 1224 pp

Gardiner, Robert, (ed) The Earliest Ships: The Evolution of Boats into Ships,

Gould, Richard, _Archaeology: And the Social History of Ship_s

Green,, Lawrence G., The Dhows of the Indian Ocean, Blue Peter 10, 1930, pp. 598-9

Greenhill, Basil, John Morrision, The Archaeology of Boats and Ships, Naval Institute Press, 1996 266 pp

Guilleux la Roerie, L., Fore-and-aft Sails in the Ancient World, MM 42 1956

Guilleux la Roerie, L., The Lateen Sail, MM 43, 1957

Hawkins, Clifford W., The Dhow - an Illustrated History of the Dhow and its World, Lymington 1977

Hornell Jams, A Tentative Classification of Arab Sea Craft, MM 28, 1942

Hourani, G. F., Direct Sailing between the Persian Gulf and China in Pre-Islamic Times, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 2, 1947

Hourani, G. F., Arab Seafaring in the Indian Ocean in Ancient and Early Medieval Times, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1951 and 1995, 189 pp.

Howarth, D., Dhows, London 1978

Jeffreys, M., Early Arab Navigation in the Indian Ocean, Islamic Review 44, 1956

Kaeyl, G., Percival, The Lateen Sail, MM 42, 1956

Koster, A., Anitke Seewesen, Berlin, 1923

Koster, A. Studien zur Geschichte des antiken Seewesens, Leipzig, 1934

Lishman, N., Arabian Lateeners, MM47, 1961

Meijer, Fik, A history of seafaring in the classical world, Croom Helm Ltd., Procident House, Kent UK, 1986

Moore, Alan, Craft on the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, MM 6, 1920

Moore Alan, Notes on Dhows, MM26, 1940

Moreland W. H., The Ships of the Arabian Sea Around 1500 AD, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1939

Muir, J., Early Arab Seafaring and Rudders, MM 51, 1965

Norton, P. J., Going about in Lateen-rigged Craft, MM 43, 1957

Oman Ministry of National Heritage and Culture, Oman a seafaring nation, Sultanate of Oman, 1991

Ormerod, Henry A, Piracy in the Ancient World: An Essay in Mediterranean History, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, 286 pp

Osborn, E. C., Tradewinds: Sail and Steam in the Gulf of Aden, Port of London Authority Magazine, September 1964

Palmer, D., Seamen of the Indian Ocean, Geographical Magazine, 4, 1936-7

Smith, G. R., The Omani Manuscript Collection at Muscat, Arabian Studies IV, 1978

Smyth, H. W., Mast and Sail in Europe and Asia, London, 1906

Sparks, E., A Muscat Dhow, Yachting Monthly, 8, page 263, 1909-10

Steffy, Richard, J., _Wooden Ship Building and the Interpretation of Shipwreck_s

Villiers, Alan, Some Aspects of the Arab Dhow Trade, Middle East Journal, 2:3, 1948

Villiers, Alan, Sailing with the Arabs, MM 49, 1963

Woodman, Richard, The History of the Ship: The Comprehensive Story of Seafaring from the Earliest Times to the Present Day

Walters, D. W., The Halyards of a Dhow, MM 32, 1946

Yajima, Hikoichi, The Arab Dhow Trade in the Indian Ocean, Preliminary Report, Institute of for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo 1976

Page Discussion

Membership is required to comment. Membership is free of charge and available to everyone over the age of 16. Just click SignUp, or make a comment below. You will need a user name and a password. The system will automatically send a code to your email address. It should arrive in a few minutes. Enter the code, and you are finished.

Members who post adverts or use inappropriate language or make disrespectful comments will have their membership removed and be barred from the site. By becoming a member you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy, Cookies & Ad Policies. Remember that we will never, under any circumstances, sell or give your email address or private information to anyone unless required by law. Please keep your comments on topic. Thanks!