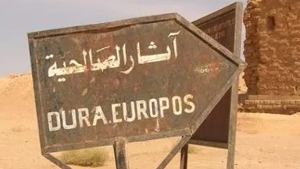

Mosque Name: Dura Europos Mosques

Country: Iraq

City: Dura Europos

Year of construction (AH): 700 - 800

Year of construction (AD): 81-183

Mosque 1: Rashidun

GPS: 34.751142 40.729486

Gibson Classification: Petra

Rebuilt facing Mecca: Never

Mosque 2: Between

GPS: 34.751142 40.729486

Rebuilt facing Mecca: Never

Description:

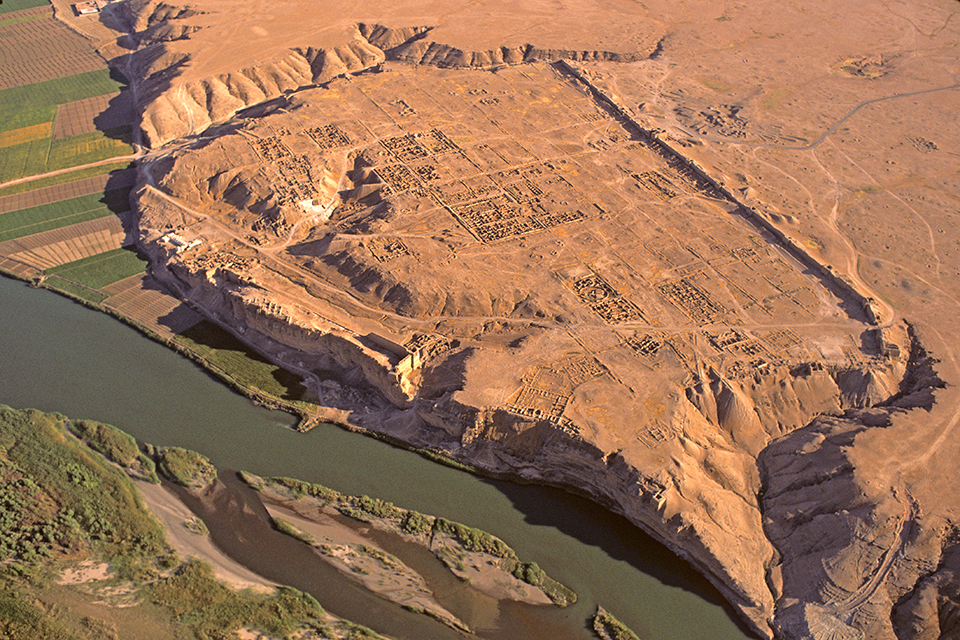

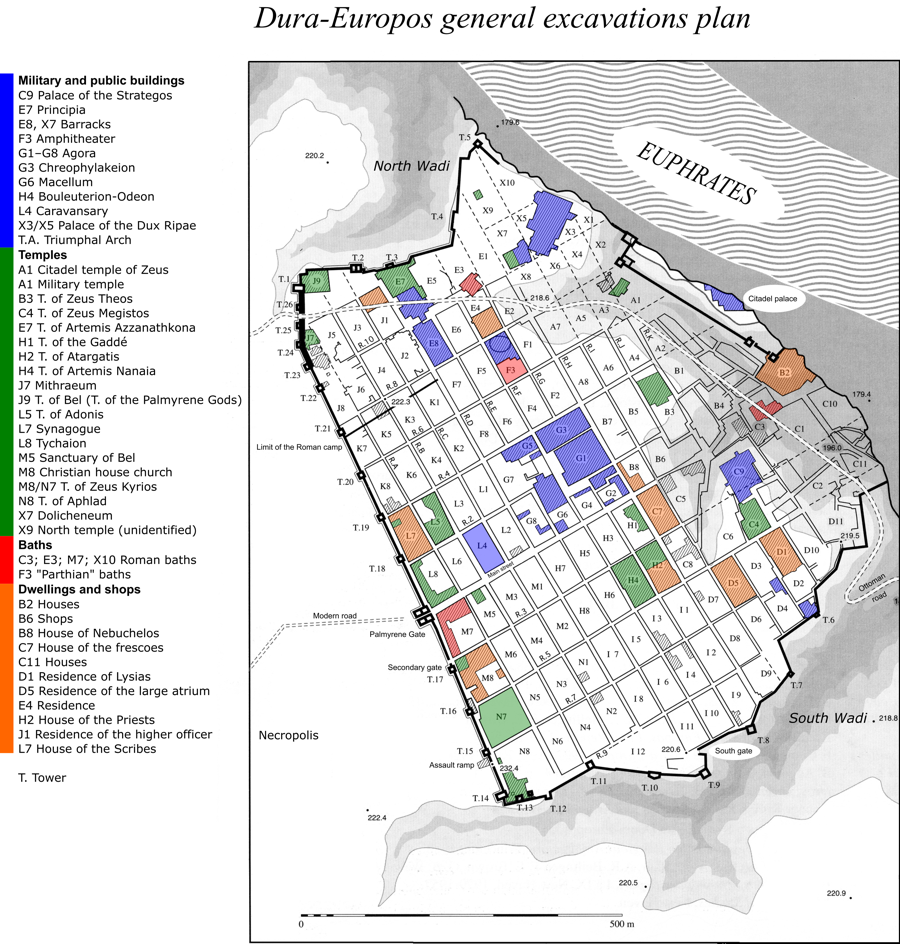

History Ancient Dura-Europos was built on the western bank of the Euphrates River at GPS: 34.748136° 40.729881° in modern Syria. The city was first called “Europos.” The Hellenistic Seleucid Empire founded the city around 300 BCE. Later, it was controlled by the Parthian Empire (2nd century BCE-later second century CE), and the Roman Empire (from the later second century CE), and known to inhabitants as “Dura” (the fortress). The modern hyphenated name Dura-Europos reflects the city’s historical and cultural complexity. During Muslim times it was simply known as Dura.

In the 250s CE, the site was the scene of battles in the Sasanian Persian wars. Roman/Byzantine soldiers garrisoned Dura and constructed a massive earthen embankment to reinforce the western wall. Buildings in the vicinity of the west wall–including a Christian church, a Jewish synagogue, and temples to various Greco-Roman and Syrian/Aramaean deities were requisitioned and filled with earth and debris, preserving them for many centuries.

Excavation European British troops stationed nearby recognized well-preserved ancient wall paintings in the 1920s, and requested assistance from an archaeologist. In Spring of 1920, the famous archaeologist James Henry Breasted happened to be on a survey of the upper Tigris river. He persuaded Colonel Arnold Talbot Wilson to make a diversion to assess the finds reported by Murphy. Breasted spent one day at the site making notes and sketches.

In 1922 Belgian archaeologist and historian Franz Cumont led two short archaeological campaigns (1922 and 1923) before the political situation made it too difficult to continue. It was not until 1928 that excavations would resume at Dura, this time sponsored jointly by the French Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Letres and Yale University, and continued for ten seasons of excavation between 1928 and 1937. The majority of artifacts from Dura today reside in collections at Yale University and the National Museum of Damascus.

For the next fifty years, little was done. Then in 1986, the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Syrian Directorate of Antiquities and Museums established the Mission Franco-Syrienne de Europos-Doura (MFSED) to carry on a joint Franco-Syrian venture aimed at the reexamination and conservation of previously-excavated remains, and limited new excavations. This ended in 2011 due to the conflict in Syria/

Mosques In 632 the early Muslim armies swept into Iraq. At the time Dura was a leading city, but none of the early maps and charts of Dura mention any mosque in the city. The archaeologists failed to note any mosque. This is understandable, because at the time, archaeologists identified mosques using two criteria. First, the building needed to face Mecca, and second it should have a mihrab niche. Since none of the structures in Dura fit this description, they assumed there was no mosque, and thus no Muslim presence in the city. This helped them conclude that Dura had ceased to be a functioning city when the Muslims arrived. It was assumed that the end of Dura as an urban settlement and military garrison came c. 256 C.E. when the Sasanians captured Dura, after a siege. The remains of a siege ramp, mines, and countermines, as well as military equipment were assumed to be Sasanian. No mention is made of the Muslim invasion and the presence of Muslims living in the city some 400 years later.

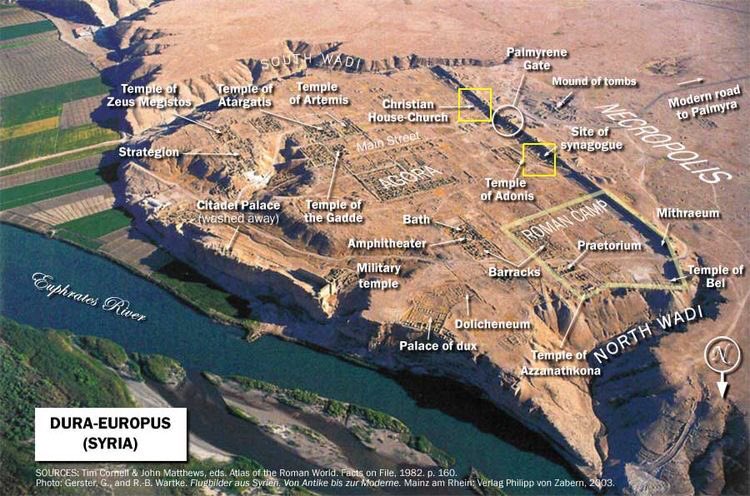

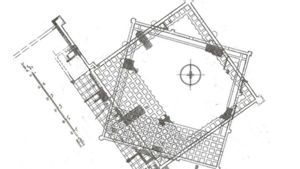

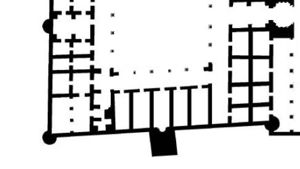

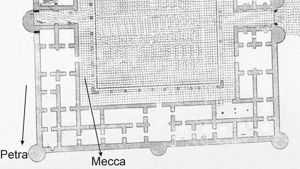

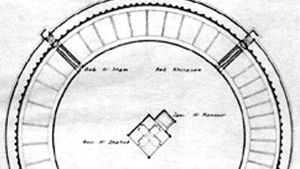

However, when Dan Gibson began releasing his survey of early mosques (first 3 centuries of Islam) to the surprise of archaeologists, he listed two mosques in Dura. One was a small Rashidun mosque, and the second was a large congregational mosque, complete with a massive mihrab. The earlier smaller Rashidun mosque was constructed before the mihrab niche was created. This small mosque faced towards ancient Petra, and it’s foundation was beneath the later congregational mosque which faced the Between qibla direction. These structures were ignored by the archaeologists who focuses on the spectacular remains left by the Jews, Romans, and Sasanians.

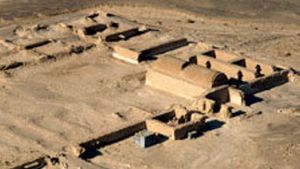

The so called Palace of Dux Ripae (Head of the River) is attached to the mosque, and faces the same Between orientation, (different from the rest of the city) and appears to be a large Umayyad Qasr. There have been no known excavations of the Qasr and accompanying mosques. This qasr was identified as the Palace of the Dux Ripae when an inscription was found, accrediting the original construction to Elagabalus (AD 218–222). The Muslims however, were known to use existing building blocks and old inscriptions in constructing their qasrs and mosques.

On the walls there were many graffiti referring to the Head of the River. Apparently at one time, Domitius Pompeianus lived in the central and largest suite that opened onto the terrace. The function of the other rooms around the courtyard were unclear to the archaeologists in their 1952 report. (M. I. Rostovtzeff et al.: Excavations at Dura Europos. 1952) The archaeologists assumed that the palace followed the standard model of the Roman Villa. However the flat roof did not belong to a Roman tradition, but was used in the later Rashidun Qasrs. Until further excavations can be done at this site.

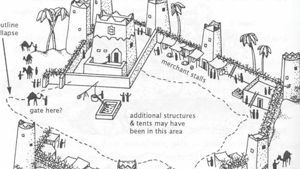

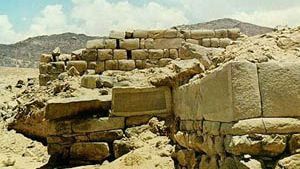

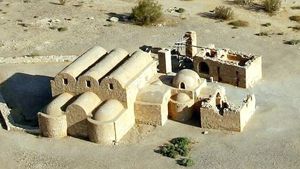

Note the qasr at the top. Below the qasr is the between-facing congregational mosque and in the center of the large congregational mosque is the foundation of the much smaller Rashidun era Petra-facing mosque.

Sketch of the Qasr and mosques.

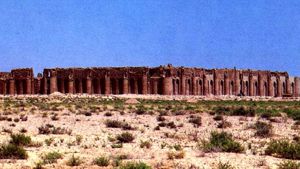

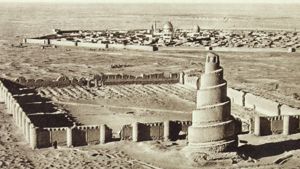

The qasr and mosques are in the lower center of the city. Photo Credit: Yale University At Gallery, https://duraeuroposarchive.org/image-rights/ Creative Commons Zero (CC0) Public Domain Statement.

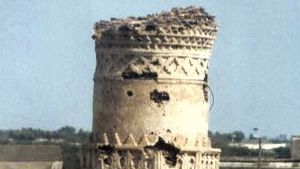

Photo Credit: Artem. G - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=115062167

The qasr and mosques are in the center lower part of the image.

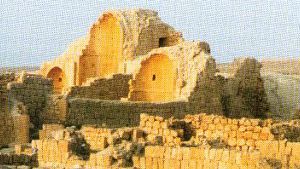

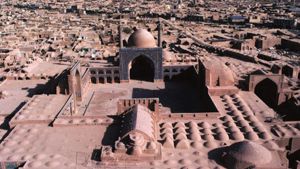

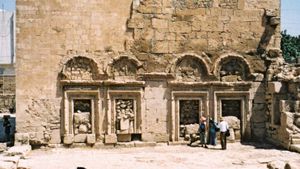

Asp/Mihrab in the so called Palace. Photo Credit: Marsyas - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4752512

Bibliography

Excavation Reports

Cumont, Franz. Fouilles de Doura-Europos (1922–1923). Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1926.

Yale-French Expedition, Preliminary Reports First Season: Baur, P. V. C., and Michael I. Rostovtzeff, eds. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters: Preliminary Report of First Season of Work, Spring 1928. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1929.

Second Season: Baur, P. V. C., and Michael I. Rostovtzeff, eds. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters: Preliminary Report of Second Season of Work, 1928–1929. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1931.

Third Season: Baur, P. V. C., Michael I. Rostovtzeff, and Alfred R. Bellinger, eds. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters: Preliminary Report of Third Season of Work, 1929–1930. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1932.

Fourth Season: Baur, P. V. C., Michael I. Rostovtzeff, and Alfred R. Bellinger, eds. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters: Preliminary Report of Fourth Season of Work, October 1930–March 1931. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1933.

Fifth Season: Rostovtzeff, Michael I., ed. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters: Preliminary Report of Fifth Season of Work, 1931–1932. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1934.

Sixth Season: Rostovtzeff, Michael I., et al., eds. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters: Preliminary Report of Sixth Season of Work, October 1932–March 1933. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1936.

Seventh and Eighth Seasons: Rostovtzeff, Michael I., Frank E. Brown, and C. Bradford Welles, eds. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters: Preliminary Report on the Seventh and Eighth Seasons of Work, 1933–1934 and 1934–1935. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1936.

Ninth Season: Rostovtzeff, Michael I., et al., eds. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters: Preliminary Report on the Ninth Season of Work, 1935–1936, Part 1: The Agora and Bazaar. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1944.

Rostovtzeff, Michael I., et al., eds. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters: Preliminary Report on the Ninth Season of Work, 1935–1936, Part 2: The Necropolis. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1946.

Rostovtzeff, Michael I., et al., eds. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters: Preliminary Report of the Ninth Season of Work, 1935–1936, Part 3: The Palace of the Dux Ripae and the Dolicheneum. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1952.

Tenth Season: Matheson, Susan B. “The Tenth Season at Dura-Europos 1936–1937,” Syria 69 (1992): 121–40. Compiled from information in the Dura-Europos Archives, Yale University Art Gallery.

Franco-Syrian Expedition, 1986–present Leriche, Pierre, et al., eds. Doura-Europos études 1986. Paris: Paul Geuthner, 1986.

______. Doura-Europos études 1988. Paris: Paul Geuthner, 1988. __ . Doura-Europos études 1990. Paris: Paul Geuthner, 1992. ____ . Doura-Europos études IV, 1991–1993. Beirut: Institut Français d’Archéologie du Proche-Orient, 1997.

Yale-French Expedition, Final Reports

Baur, P. V. C. The Lamps. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters, Final Report 4, Part 3, ed. Michael I. Rostovtzeff et al. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1947.

Bellinger, Alfred R. The Coins. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters, Final Report 6, ed. Michael I. Rostovtzeff et al. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1949.

Clairmont, Christoph W. The Glass Vessels. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters, Final Report 4, Part 5, ed. Ann Perkins. New Haven, Conn.: Dura-Europos Publications, 1963.

Cox, Dorothy H. The Greek and Roman Pottery. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters, Final Report 4, Part 1, Fascicle 2, ed. Michael I. Rostovtzeff et al. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1949.

Downey, Susan B. The Stone and Plaster Sculpture. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters, Final Report Volume 3, Part 1, Fascicle 2. Los Angeles: Institute of Archaeology, University of California, 1977. ____ . The Heracles Sculpture. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Arts and Letters, Final Report 3, Part 1, Fascicle 1, ed. C. Bradford Welles. New Haven, Conn.: Dura-Europos Publications, 1969.

Dyson, Stephen L. The Commonware Pottery: The Brittle Ware. The Excavations at DuraEuropos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters, Final Report 4, Part 1, Fascicle 3, ed. C. Bradford Welles. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1968.

Frisch, Teresa G., and Nicholas Toll. The Bronze Objects: Pierced Bronzes, Enameled Bronzes, and Fibulae. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters, Final Report Volume 4, Part 4, Fascicle 1, ed. Michael I. Rostovtzeff et al. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1949.

James, Simon T. The Arms and Armour, and Other Military Equipment. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters, Final Report 7. London: British Museum Press, 2004.

Kraeling, Carl H. The Christian Building. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters, Final Report 8, Part 2, ed. C. Bradford Welles. New Haven, Conn.: Dura-Europos Publications, 1967.

____. The Synagogue. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters, Final Report 8, Part 1, ed. Alfred R. Bellinger et al. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1956.

Pfister, R., and Louisa Bellinger. The Textiles. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters, Final Report 4, Part 2, ed. Michael I. Rostovtzeff et al. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1945.

Toll, Nicholas. The Green Glazed Pottery. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters, Final Report 4, Part 1, Fascicle 1, ed. Michael I. Rostovtzeff et al. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1943.

Welles, C. Bradford, R. O. Fink, and J. F. Gilliam, eds. The Parchments and Papyri. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters, Final Report Volume 5, Part 1. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1959.

General References

Baird, Jennifer A. “Constructing Dura-Europos, Ancient and Modern.” In Roman Spaces, Heritage Traces: Past and Present Roman Place-Making, ed. Corisande Fenwick, Kathryn Lafrenz Samuels, and Darian Totten. Portsmouth, R.I.: Journal of Roman Archaeology, forthcoming.

____ . “Housing and Households at Dura-Europos: A Study in Identity on Rome’s Eastern Frontier.” Ph.D. diss., University of Leicester, 2006.

____ . “Shopping, Eating, and Drinking at Dura-Europos: Reconstructing Contexts.” In Objects in Context, Objects in Use: Material Spatiality in Late Antiquity, ed. Luke Lavan, Ellen Swift, and Toon Putzeys. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2007, 413–37.

Breasted, James Henry. The Oriental Forerunners of Byzantine Painting: First-Century Wall Paintings from the Fortress of Dura on the Middle Euphrates. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1924.

Butcher, Kevin. Roman Syria and the Near East. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2003.

Cumont, Franz. “The Dura Mithraeum.” In Mithraic Studies: Proceedings of the First International Congress of Mithraic Studies, ed. J. R. Hinnels. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1975, 1:151–214.

Dirven, Lucinda. The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: A Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 1999

Downey, Susan B. Terracotta Figurines and Plaques from Dura-Europos. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003.

Elsner, Jas. “Cultural Resistance and the Visual Image: The Case of Dura Europos.” Classical Philology 96 (2001): 269–304.

____ . “Viewing and Resistance: Art and Religion in Dura Europos.” In Roman Eyes: Visuality and Subjectivity in Art and Text, ed. Jas Elsner. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2007: 253–87.

Fine, Steven, ed. Sacred Realm: The Emergence of the Synagogue in the Ancient World. New York: Yeshiva University Museum, 1996.

Frye, Richard N., et al. “Inscriptions from Dura-Europos.” Yale Classical Studies 14 (1955): 123–213.

Gutmann, Joseph, ed. The Dura-Europos Synagogue: A Re-evaluation (1932–1992). Atlanta, Ga.: Scholars Press, 1992.

Hopkins, Clark. “The Palmyrene Gods at Dura-Europos.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 51, no. 2 (1931): 119–37.

____ . “The Siege of Dura,” Classical Journal 42 (1947): 251–59.

____ . The Discovery of Dura-Europos, ed. Bernard Goldman. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1979.

Levine, Lee I., and Ze’ev Weiss, eds. From Dura to Sepphoris: Studies in Jewish Art and Society in Late Antiquity. Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplement 40. Portsmouth, R.I.: Journal of Roman Archaeology, 2000.

MacDonald, David. “Dating the Fall of Dura-Europos.” Historia 35 (1986): 45–68.

Matheson, Susan B. Dura-Europos: The Ancient City and the Yale Collection. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 1982.

Millar, Fergus. The Roman Near East, 31 b.c.–a.d. 337. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Perkins, Ann. The Art of Dura-Europos. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973.

Pollard, Nigel. Soldiers, Cities, and Civilians in Roman Syria. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000.

Rostovzeff, Michael I. “Dura and the Problem of Parthian Art.” Yale Classical Studies 5 (1935): 155–304.

Weitzmann, Kurt, and Herbert L. Kessler. The Frescoes of the Dura Synagogue and Christian Art. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1990.

Welles, C. Bradford. “The Population of Roman Dura.” In Studies in Roman Economic and Social History in Honor of Allan Chester Johnson, ed. P. R. Coleman-Norton. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1951, 251–74.

____ . “The Gods of Dura-Europos.” In Beiträge zur alten geschichte und deren nachleben: Festschrift für Franz Altheim zum 6.10.1968, ed. Ruth Stiel and Hans Erich Stier. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter and Co., 1970, 50–65.

Wharton, Annabel Jane. Refiguring the Post Classical City: Dura Europe, Jerash, Jerusalem, and Ravenna. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Page Discussion

Membership is required to comment. Membership is free of charge and available to everyone over the age of 16. Just click SignUp, or make a comment below. You will need a user name and a password. The system will automatically send a code to your email address. It should arrive in a few minutes. Enter the code, and you are finished.

Members who post adverts or use inappropriate language or make disrespectful comments will have their membership removed and be barred from the site. By becoming a member you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy, Cookies & Ad Policies. Remember that we will never, under any circumstances, sell or give your email address or private information to anyone unless required by law. Please keep your comments on topic. Thanks!